Volume 12, Issue 1 (3-2023)

JCHR 2023, 12(1): 42-51 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Kalantari M, Zareei Mahmoodabadi H, Sedrpooshan N. A Qualitative Study on Prolonged Grief for the Loss of Spouse in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring Lived Experience. JCHR 2023; 12 (1) :42-51

URL: http://jhr.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-872-en.html

URL: http://jhr.ssu.ac.ir/article-1-872-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, Islamic Azad University, Yazd Branch, Yazd, Iran

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran ,mailto:Zareei_h@yahoo.com

2- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran ,

Full-Text [PDF 295 kb]

(1287 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1189 Views)

Maryam Kalantari 1 , Hassan Zareei Mahmood Abadi 2*, Najmeh Sedrpoushan 1

How to cite this paper:

Kalantari M, Zareei Mahmood Abadi H, Sedrpoushan N. A Qualitative Study on Prolonged Grief for the Loss of Spouse in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring Lived Experience. J Community Health Research 2023; 12(1): 42-51.

Introduction

References

1. Howarth R. Concepts and controversies in grief and loss. Journal of mental health counseling. 2011; 33(1): 4-10.

2. Malkinson R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of grief: A review and application. Research on Social Work Practice. 2001; 11(6): 671-698.

3. Seddighi Z, Soltani S. Prevalence of psychological disorders and mental health in working women with school children during the Covid-19 era. The first national conference on the production of health knowledge in the face of corona and governance in the post-corona world: undefined; 2021.

4. Keshvardoost S, Bahaadinbeigy K, Fatehi F. Role of telehealth in the management of COVID-19: lessons learned from previous SARS, MERS, and Ebola outbreaks. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2020.

5.Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, et al. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2020; 74(4): 281-282.

6. Yin X, Wang J, Feng J, et al. The Impact of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 Outbreak on Chinese Residents’ Mental Health. Available at SSRN 3556680. 2020.

7. Hoseini E, Zare F. Application of E-health in Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Journal of Community Health Research. 2020; 9(2): 66-68.

8. Shear K, Monk T, Houck P, et al. An attachment-based model of complicated grief including the role of avoidance. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2007; 257(8): 453-461.

9. Tang S, Xiang Z. Who suffered most after deaths due to COVID-19 prevalence and correlates of prolonged grief disorder in COVID-19 related bereaved adults? Globalization and health. 2021; 17(1): 1-9.

10. Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, et al. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders. 2017; 212: 138-149.

11. Eisma MC, Boelen PA, Lenferink LI. Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 288: 113031.

12. Johns L, Blackburn P, McAuliffe D. COVID-19, prolonged grief disorder and the role of social work. International Social Work. 2020; 63(5): 660-4.

13. Ingles J, Spinks C, Yeates L, et al. Posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief after the sudden cardiac death of a young relative. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(3): 402-405.

14. Boelen PA, van Denderen M, de Keijser J. Prolonged grief, posttraumatic stress, anger, and revenge phenomena following homicidal loss: the role of negative cognitions and avoidance behaviors. Homicide Studies. 2016; 20(2): 177-195

15. He L, Tang S, Yu W, et al. The prevalence, comorbidity and risks of prolonged grief disorder among bereaved Chinese adults. Psychiatry research. 2014; 219(2): 347-352.

16. Wanna R, Lueboonthavatchai P. Prevalance of complicated grief and associated factors in psychiatric outptients at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Journal of the Psychiatric Association of Thailand. 2015; 60(2): 85-98.

17. Djelantik AMJ, Smid GE, Mroz A, et al. The prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in bereaved individuals following unnatural losses: Systematic review and meta regression analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020; 265: 146-156.

18.Yi X, Gao J, Wu C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of prolonged grief disorder among bereaved survivors seven years after the Wenchuan earthquake in China: a cross-sectional study. International journal of nursing sciences. 2018; 5(2): 157-161.

19. Fujisawa D, Miyashita M, Nakajima S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of complicated grief in general population. Journal of affective disorders. 2010; 127(1-3): 352-358.

20. Maxfield M, John S, Pyszczynski T. A terror management perspective on the role of death-related anxiety in psychological dysfunction. The Humanistic Psychologist. 2014; 42(1): 35-53.

21. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry, 11th ed: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

22. Worden JW. Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner: springer publishing Company; 2019. 293 pp.

23. Lenferink LI, Eisma MC, Smid GE, et al. Valid measurement of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder and DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 prolonged grief disorder: The Traumatic Grief Inventory-Self Report Plus (TGI-SR+). Comprehensive psychiatry. 2022; 112: 152281.

24. Faramarzi S, Asgari K, Taghavi FJRiBS. The effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on the rate of high school students with abnormal grief. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences. 2013; 5: 373-382.

25. Goveas JS, Shear MK. Grief and the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2020; 28(10): 1119-25.

26. Azim Oghlui Oskooi PB, farahbakhsh K, moradi O. Effective fields the experience of mourning after the death of a family member: A phenomenological study %J Counseling Culture and Psycotherapy. 2020; 12(45): 117-160.

27. Blankmeyer K, Hackathorn J, Bequette AW, et al. Till death do we part: Effects of mortality salience on romantic relationship factors. Unpublished manuscript, Saint Louis University. 2011.

28. Spitzenstätter D, Schnell T. Effects of mortality awareness on attitudes toward dying and death and meaning in life—a randomized controlled trial. Death Studies. 2020: 1-15.

29. Yousefi P, Ghelichpoor S, zadeh AAH, et al. The effect of coronavirus pneumonia 2019 on long-term grief disorder: A review study. The second research congress of students of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences. 2021.

30. Diolaiuti F, Marazziti D, Beatino MF, et al. Impact and consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on complicated grief and persistent complex bereavement disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2021; 300: 113916.

31. Ahmadi K, Darabi A. The effectiveness of patience training on reducing grief and facilitating posttraumatic growth. Cultural Psychology. 2017; 1(1): 114-31.

32. Mortazavi SS, Assari S, Alimohamadi A, et al. Fear, loss, social isolation, and incomplete grief due to COVID-19: a recipe for a psychiatric pandemic. Basic and clinical neuroscience. 2020; 11(2): 225.

33. Nobahari A, Fathi E, Malekshahi Beiranvand F, et al. The Death awareness and Spiritual Experience of Health Care Workers during COVID-19 Outbreak. Journal of Community Health Research 2022; 11(1): 31-35.

34. Colaizzi PF, Valle RS, King M. Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. 1978; 48-71.

35. Esmaeilpour K, Bakhshalizadeh Moradi S. The Severity of Grief Reactions Following Death of First-Grade Relatives. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2015; 20(4): 363-371.

36. Creswell JW. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative: Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ; 2002.

37. Pérez HCS, Ikram MA, Direk N, et al. Prolonged grief and cognitive decline: a prospective population-based study in middle-aged and older persons. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2018; 26(4): 451-460.

38. Niknami M. Abbaspour A. Taghavifard M. et al. Methods of Improving the Dimensions of Psychological Empowerment of Employees of SAMT Organization in the Condition of COVID-19. Management Studies in Development and Evolution.2022; 102(30): 7-35.

39. Dehaghani FA. Evaluation of COVID-19 mourning and available treatment methods. First National Conference on Cognitive Science and Education: undefined; 2021.

Full-Text: (949 Views)

| A Qualitative Study on Prolonged Grief for the Loss of Spouse in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring Lived Experience |

Maryam Kalantari 1 , Hassan Zareei Mahmood Abadi 2*, Najmeh Sedrpoushan 1

- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities, Islamic Azad University, Yazd Branch, Yazd, Iran

- Department of Psychology and Educational Sciences, Yazd University, Yazd, Iran

| ARTICLE INFO | ABSTRACT | |

| Original Article

Received: 13 February 2022

Accepted: 12 October 2022 |

Background: Millions of people's lives, as well as their physical and mental health, were put in jeopardy when COVID-19 emerged. The pandemic resulted in a high death rate. Health protocols prevented the bereaved from attending the funeral. As a result, many people faced unfinished mourning. This study was conducted with the aim of identifying the meaning of mourning and the strategies used by bereaved spouses

Methods: The research method was qualitative and based on descriptive phenomenological strategy. Among the bereaved people who met the criteria to enter the research, 15 people were selected using the purposeful sampling method and using semi-structured interviews until saturation was reached. The data were coded using the Colaizi method and finally the results were analyzed using the MAXQDA software.

Results: After extracting the research findings in the form of 460 concepts, 27subcategories, and 9 main categories, they were represented as an educational package. Major themes were the obligation to hold mourning, social feedback from others, gradual healing, the experience of widowhood, existential emptiness, psychological collapse, the progressive repercussions of widowhood, and comprehensive self-talk about complicated pathological

effects of death and mourning Conclusion: Considering Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the lack of mourning for the loss of a spouse, health care practitioners must address these women's psychological and social needs. Thus, knowing these problems can assist health care workers and bereaved women's families in minimizing the psychological challenges of acute sorrow.

Keywords: Bereaved people, Phenomenology, Grief |

|

|

Corresponding Author:

Zareei Mahmood Abadi H zareei_h@yahoo.com |

Kalantari M, Zareei Mahmood Abadi H, Sedrpoushan N. A Qualitative Study on Prolonged Grief for the Loss of Spouse in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Exploring Lived Experience. J Community Health Research 2023; 12(1): 42-51.

Introduction

Death is the most unforeseen event in human beings' lives. The most difficult challenge man faces is coping with the death of loved ones (1). Grief is a universal human reaction, occurring across all cultures and age groups in response to various sorts of loss, most notably the death of a loved one (2). At the end of 2019, a new infectious illness caused by a novel coronavirus was found in China. Not only did this sickness generate public health issues, but also resulted in various psychological ailments such as anxiety, depression, stress disorders, sleep abnormalities, and obesity (3).

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19), which has become a global health disaster ever since (4). Acute respiratory symptoms are one of the most common symptoms of COVID-19, and in 2% of cases, it leads to the patient's death (5). Studies have shown that with the prevalence of COVID-19, anxiety and depression symptoms in 2019 were increased by 15% and 11%, respectively (6). However, the virus's damage does not end with death. It significantly damages the families of these patients, who do not have the opportunity to mourn or express their emotions and grief since they were in quarantine for an extended period following the beloved's death. At the same time, they were unable to communicate with other relatives (7). In addition, their families cannot grieve when they need to, which leads to rumination throughout the quarantine time (8). Globally, COVID-19 has left approximately 16 million mourners. If the deaths of close friends were also included, this figure would be substantially higher (9). 9.8% of people will develop prolonged grief disorder (PGD) after losing a loved one (10).

Researchers have expressed concerns that COVID-19's associated mortality situations are increasing the frequency of PGD worldwide (11, 12). Prolonged grieving symptoms were shown to be more prevalent in Australia (13), the Netherlands (14), China (15) and Thailand (16). Furthermore, grief over losing a person to COVID-19 is detrimental because it will make people see the outbreak as a catastrophe (17). The traumatic nature of COVID-19 deaths worsens by not meeting the dying person and the failure to hold or participate in traditional funerals and other rituals (18). Death is highly threatening for many people; the subsequent anxiety is called death anxiety (19). It includes the fear of death regarding both the individuals and the beloved. According to the existential psychotherapy, the desire to survive when considering the inevitability of death causes anxiety (20).

Mourning can be defined as the response and reaction to the loss of a person or thing that belongs to a particular group. Regarding psychological reactions, grieving refers to the emotions resulting from the death of a loved one. Although complicated grief is not considered a mental illness, some individuals who experience complicated grief eventually develop major depression disorders (21). When some features of natural grief become psychotic due to distortion or exaggeration, abnormal mourning arises (22). According to mental health experts, it is necessary that long-term and post-epidemic grieving be addressed. While most individuals can cope with sadness and move on with their life, others cannot, and suffer from complicated grief (23). This disorder manifests itself in the following ways: an intense focus on the loss and intense longing for the lost person, struggling with sad feelings, inability to enjoy life, depression, and difficulty performing routine tasks, withdrawal from social activities, irritability, aggression, and distrust of others (24). The findings of research on grieving among the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that mourners needed help, and educating counselors and psychiatrists was highly beneficial in decreasing grief and sadness (25). Another qualitative phenomenological study conducted on the effective factors regarding the experience of grief after the death of a family member shows four effective main themes, including family contexts, personal contexts, attitudes in the context, and cultural contexts (26).

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the spread of Coronavirus (COVID-19), which has become a global health disaster ever since (4). Acute respiratory symptoms are one of the most common symptoms of COVID-19, and in 2% of cases, it leads to the patient's death (5). Studies have shown that with the prevalence of COVID-19, anxiety and depression symptoms in 2019 were increased by 15% and 11%, respectively (6). However, the virus's damage does not end with death. It significantly damages the families of these patients, who do not have the opportunity to mourn or express their emotions and grief since they were in quarantine for an extended period following the beloved's death. At the same time, they were unable to communicate with other relatives (7). In addition, their families cannot grieve when they need to, which leads to rumination throughout the quarantine time (8). Globally, COVID-19 has left approximately 16 million mourners. If the deaths of close friends were also included, this figure would be substantially higher (9). 9.8% of people will develop prolonged grief disorder (PGD) after losing a loved one (10).

Researchers have expressed concerns that COVID-19's associated mortality situations are increasing the frequency of PGD worldwide (11, 12). Prolonged grieving symptoms were shown to be more prevalent in Australia (13), the Netherlands (14), China (15) and Thailand (16). Furthermore, grief over losing a person to COVID-19 is detrimental because it will make people see the outbreak as a catastrophe (17). The traumatic nature of COVID-19 deaths worsens by not meeting the dying person and the failure to hold or participate in traditional funerals and other rituals (18). Death is highly threatening for many people; the subsequent anxiety is called death anxiety (19). It includes the fear of death regarding both the individuals and the beloved. According to the existential psychotherapy, the desire to survive when considering the inevitability of death causes anxiety (20).

Mourning can be defined as the response and reaction to the loss of a person or thing that belongs to a particular group. Regarding psychological reactions, grieving refers to the emotions resulting from the death of a loved one. Although complicated grief is not considered a mental illness, some individuals who experience complicated grief eventually develop major depression disorders (21). When some features of natural grief become psychotic due to distortion or exaggeration, abnormal mourning arises (22). According to mental health experts, it is necessary that long-term and post-epidemic grieving be addressed. While most individuals can cope with sadness and move on with their life, others cannot, and suffer from complicated grief (23). This disorder manifests itself in the following ways: an intense focus on the loss and intense longing for the lost person, struggling with sad feelings, inability to enjoy life, depression, and difficulty performing routine tasks, withdrawal from social activities, irritability, aggression, and distrust of others (24). The findings of research on grieving among the elderly during the COVID-19 pandemic indicated that mourners needed help, and educating counselors and psychiatrists was highly beneficial in decreasing grief and sadness (25). Another qualitative phenomenological study conducted on the effective factors regarding the experience of grief after the death of a family member shows four effective main themes, including family contexts, personal contexts, attitudes in the context, and cultural contexts (26).

Researchers in a study indicated that death awareness leads to the improvement and promotion of family relationships and improved physical health (27). When people become aware of death, their anxiety decreases, and they become more accepting (28). In another study, the findings revealed that communication limitations during the outbreak interfere with a successful passage through the stages of mourning and cause depression in community members (29). Moreover, Diolaiuti's et al. research on complicated grief revealed that the rapid identification of risk factors and protective features through screening and prevention programs is very important due to the traumatic conditions of quarantine (30). Since the lack of mourning phase naturally impairs a person's individual and social activities, several attempts have been made to identify techniques for overcoming sadness (31). Mourning is a psycho-physiological process which takes time. Non-acceptance of loss results in complicated grief (CG), a condition in which avoidance of mourning, anger, shame, remembering the person's death, and not having a key role in that condition contribute to the unfinished grief (32).

The COVID-19 pandemic and communication restrictions imposed by the government to prevent the further spread of the disease have had a profound effect on the mourning process. Given the importance of acceptance and coping with grief to return to normal life, especially in social quarantine and the reduced support for the grieving person, the gap in research in this field is felt. This qualitative phenomenological study explores the lived experiences of women mourning the loss of their loved ones to COVID-19 (33). The phenomenological method is necessary because it describes the meanings of a concept or phenomenon through the individuals' lived experiences. It also involves understanding people's shared experiences by providing factual information which helps the researcher examine and describe them without prejudice. This research can be used as a guide for the mourning public to start a new identity and life. The results can also be used for the grief caused by the relatives' suicide and death due to other infectious diseases such as AIDS and hepatitis. Therefore, this study examines the lived experiences of mourning spouses who lost their partners to COVID-19 in Yazd.

The COVID-19 pandemic and communication restrictions imposed by the government to prevent the further spread of the disease have had a profound effect on the mourning process. Given the importance of acceptance and coping with grief to return to normal life, especially in social quarantine and the reduced support for the grieving person, the gap in research in this field is felt. This qualitative phenomenological study explores the lived experiences of women mourning the loss of their loved ones to COVID-19 (33). The phenomenological method is necessary because it describes the meanings of a concept or phenomenon through the individuals' lived experiences. It also involves understanding people's shared experiences by providing factual information which helps the researcher examine and describe them without prejudice. This research can be used as a guide for the mourning public to start a new identity and life. The results can also be used for the grief caused by the relatives' suicide and death due to other infectious diseases such as AIDS and hepatitis. Therefore, this study examines the lived experiences of mourning spouses who lost their partners to COVID-19 in Yazd.

Methods

This was a qualitative study which used descriptive phenomenological strategies. The qualitative method was used due to the appropriateness of qualitative methods in discovering the complexities and hidden angles of a phenomenon. In this regard, the researcher tried to discover the dominant processes in the social context from the perspective of the subjects and did not limit his research to the mere explanation of the data and units under investigation. The sampling method used was theoretical and purposive. The study population included mourning women from Yazd who lost their husbands due to COVID-19 in 2021. The criteria for entering the research included: 1. Willingness to interview and cooperate. 2. Dissatisfaction with existing situation and experience. 3. Being married (no legal divorce). Through semi-structured interviews and targeted sampling of those women who had experienced bereavement for 6 to 12 months, with a moderate to severe bereavement score, 30 people were selected. Interviews were conducted free of charge, and the privacy of individuals was respected. After 15 interviews, saturation was reached. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the interviewees.

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants

| Interviewee's group | Grieving women who lost their husbands |

| Satisfaction | Agreed to conduct the interview |

| Participant's age | 27 to 48 years old (under 50) |

| Interview's type | Deep semi-structured |

| Number | 15 |

Interviews were conducted after assuring the participants about the confidentiality of their words, information, and identity. Due to the prevalence of COVID-19 and the difficulties associated with face-to-face communication, the interviews were conducted both in-person and online (by email, WhatsApp, or phone). After categorizing the material, the researcher referred to each participant's recorded speech several times to make the interview accurate. After classifying the information, the researcher repeatedly referred to the participant to validate it. The researchers, then, extracted and coded the data. Data collection and analysis were carried out using Colaizzi's seven-step method.

1. Each interview sheet should be read and re-read to understand the material thoroughly.

2. Significant terms relating to the studied phenomena should be extracted from each text. Then, these phrases and sentences should be coded again on another page.

3. The essence of these significant sentences should be extracted and expressed.

4. Clusters and themes should be used to classify the retrieved meaning.

5. The study results should be combined into a thorough descriptive format which accurately portrays all of the observed phenomenon's characteristics.

6. The clusters' overall structure and extracted themes should be re-examined.

7. Another evaluator should determine the validity and reliability of clusters and categories. Finally, the researchers must share their interpretation of the interviews with the interviewees to confirm the validity of the findings (34).

Analysis method

Data were analyzed using Colaizzi's seven-step method and advanced software for qualitative data analysis (MAXQDA).

Results

2. Significant terms relating to the studied phenomena should be extracted from each text. Then, these phrases and sentences should be coded again on another page.

3. The essence of these significant sentences should be extracted and expressed.

4. Clusters and themes should be used to classify the retrieved meaning.

5. The study results should be combined into a thorough descriptive format which accurately portrays all of the observed phenomenon's characteristics.

6. The clusters' overall structure and extracted themes should be re-examined.

7. Another evaluator should determine the validity and reliability of clusters and categories. Finally, the researchers must share their interpretation of the interviews with the interviewees to confirm the validity of the findings (34).

Analysis method

Data were analyzed using Colaizzi's seven-step method and advanced software for qualitative data analysis (MAXQDA).

Results

After extracting the themes from the study data, 460 concepts, 27 sub-categories, and nine main categories were obtained. Major themes included an obligation to hold mourning, social feedback from others, the gradual exit from grieving, the experience of widowhood, existential emptiness, psychological collapse, the progressive repercussions of widowhood, and comprehensive self-talk about complicated pathological death and mourning.

Table 2. Extracting concepts and main categories

| Main categories | Sub-categories |

| 1. Obligation to hold mourning | Mourning ceremonies, traumatic crisis |

| 2. Social feedback from others | Striving for companionship, accumulation of sorrow and regret, silent and heavy grief |

| 3. The gradual exit from grieving | Denial, anger, bargaining, acceptance |

| 4. The experience of widowhood | Sustained grief, being judged by others, staying alone |

| 5. Existential emptiness | The disappearance of presence, the tragedy of isolation, the bitter turmoil |

| 6. Psychological collapse | Suffering loneliness |

| 7. The progressive repercussions of widowhood | Gradual psychological vulnerability, lack of planning, psychological support, experiencing frustration, helplessness, failure, and lack of motivation |

| 8. Comprehensive self-talk about death | Dark perception, vague shadow, black nature |

| 9. Complex and pathological grief | Sudden absence, the symptom of grief |

1. Obligation to hold mourning

One significant aspect of death due to COVID-19 is eliminating communications, rituals, burials, and collective mourning. There were no funerals or burials for deceased people with COVID-19 because of the risk of spreading the disease. The absence of collective mourning and its rituals will ultimately result in unspoken grief. The participants wanted to express their grief caused by the catastrophic crisis via rituals. Their failure brought them a feeling of sorrow that lingered in their hearts forever and seemed to signify incomplete grieving.

Participant (6): I want the COVID-19 pandemic to end, and I want to have a ceremony for my husband, a normal mourning.

Participant (6): I want the COVID-19 pandemic to end, and I want to have a ceremony for my husband, a normal mourning.

2. Social feedback from others

If the grieving period is finished and these steps are followed, the individuals can return to the community and continue their daily life during the recovery phase. This scenario depends on time and people's external circumstances; coping happens more quickly if a person is psychologically supported. Conversely, the longer they are left alone, the slower the adjustment occurs. The critical point is that mourning symptoms are not distinct and can occur concurrently.

Participant (3): The presence of family and relatives who helped me perform rituals, commute, and take care of the children was so comforting. I felt better when I visited my husband in the hospital during his stay; my husband insisted that it was unnecessary, but I went anyway.

Participant (3): The presence of family and relatives who helped me perform rituals, commute, and take care of the children was so comforting. I felt better when I visited my husband in the hospital during his stay; my husband insisted that it was unnecessary, but I went anyway.

3. Gradual exit from grieving

Grief is a normal human reaction to loss. While grieving, every emotion is acceptable; there is no right or wrong feeling. In mourning, people often experience sadness, shock, denial or disbelief, confusion, anger, bargaining, emotions of freedom, and acceptance. Accepting that the departed will not return is the first step in alleviating sorrow and loss. Unpleasant feelings should not be suppressed and talking about both good and bad memories and emotions associated with the deceased person will significantly improve the mourning stage. Crying assists in the discharge of undesirable emotions and should not be avoided.

Participant (7): When someone puts the key in the door lock, I think it is my husband at the door; his voice is still in my head; why should I be a widow this early? Why should my husband die at such a young age when it was obvious that he was not ready to go? I do not believe my beloved has died because we did not hold a mourning ceremony. I still think he is on his way.

Participant (11): I hate the damn COVID. Everything was going well but sudden COVID-19 appeared, and a huge storm took away our opportunity.

Participant (11): I hate the damn COVID. Everything was going well but sudden COVID-19 appeared, and a huge storm took away our opportunity.

4. Widowhood experience

The experience of widowhood is contingent upon various aspects, including the nature of the psychological distress itself (such as the situation in which the distress occurs), estimation and evaluation of the situation, and the person's resources to cope with the condition. The participants interpreted this unpleasant incident in two very different ways, depending on the meaning attached to the scenario in their minds.

Participant (1): The feeling that others look at you with pity and think that you become miserable bothers me. Some acted compassionately and nodded along. They were also annoying.

Participant (1): The feeling that others look at you with pity and think that you become miserable bothers me. Some acted compassionately and nodded along. They were also annoying.

5. Existential emptiness

Losing a loved one is the most significant event in a person's life and results in an emotional crisis. This loss resulted in a profound sense of existential emptiness and misery, manifested as that person's absence, the tragedy of solitude, and painful conflict, all of which affected the participants' behavior and performance.

Participant (10): There is a big hole, an emptiness inside me; I have to work outside and support my daughter, who was dependent on her father, and I have to look after myself, too.

Participant (10): There is a big hole, an emptiness inside me; I have to work outside and support my daughter, who was dependent on her father, and I have to look after myself, too.

6. Mental breakdown

The participants' anxiety disorders and loneliness exhibited not just dysfunction but also panic, despair, and alienation due to their loneliness.

Participant (5): Husbands and wives strive their whole lives to assist one another till they get old, but I am now alone and left without a family. There was no mourning. Funerals were conducted at a distance, and disinfectants applied to corpses (lime) made me even sadder.

Participant (5): Husbands and wives strive their whole lives to assist one another till they get old, but I am now alone and left without a family. There was no mourning. Funerals were conducted at a distance, and disinfectants applied to corpses (lime) made me even sadder.

7. Gradual consequences of widowhood

Every married man and woman will experience widowhood or the loss of a spouse (with the death of a spouse). Women's widowhood has consequences in three dimensions: psychological, social, and economic.

Participant (6): I cannot leave the house. I always went to the mosque, went shopping, and visited relatives with my husband. The sound of the call to prayer makes me cry. I weep because we went to the mosque together. I also do not know how to drive, and it is difficult for me to ask my children to do my shopping.

Participant (6): I cannot leave the house. I always went to the mosque, went shopping, and visited relatives with my husband. The sound of the call to prayer makes me cry. I weep because we went to the mosque together. I also do not know how to drive, and it is difficult for me to ask my children to do my shopping.

8. Comprehensive self-talk about death

Participants who lost their spouses during the COVID-19 encountered numerous difficulties because they did not have mourning ceremonies; as a result, they developed their own definitions and perceptions. They used various terms such as dark perception, obscured shadow, and black nature, and uttered all kinds of self-talk about death.

Participant (3): It happened at a horrible time. I do not know what I should do now, what the future holds, or what I should do financially; I have no idea about the future. I am unfamiliar with financial matters and am unsure how to handle tasks outside home. I feel that I cannot handle them.

Participant (3): It happened at a horrible time. I do not know what I should do now, what the future holds, or what I should do financially; I have no idea about the future. I am unfamiliar with financial matters and am unsure how to handle tasks outside home. I feel that I cannot handle them.

9. Complex and pathological grief

Complex mourning can sometimes be complicated and affect a person's entire life.

Participants (6) and (7): My hands and feet are numb; I cannot wash a single garment or dish. Now that I'm feeling a bit better, I'm worried. I cannot sleep. My body hurt, I felt like I was being forced to move, my blood pressure increased, and I am on medication now. I keep forgetting things. For example, I asked my mother why she did not call me; she said I called you this morning.

Participants (6) and (7): My hands and feet are numb; I cannot wash a single garment or dish. Now that I'm feeling a bit better, I'm worried. I cannot sleep. My body hurt, I felt like I was being forced to move, my blood pressure increased, and I am on medication now. I keep forgetting things. For example, I asked my mother why she did not call me; she said I called you this morning.

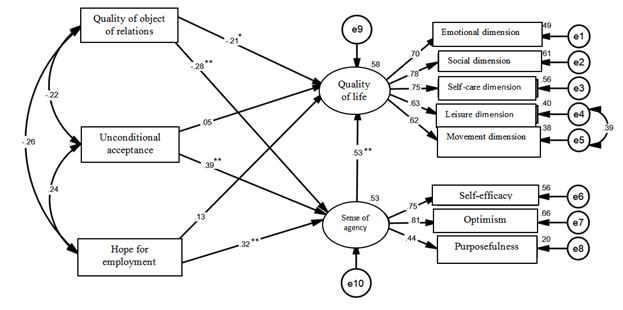

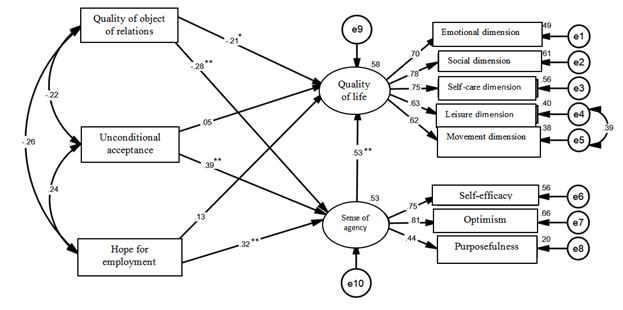

Figure 1. Categories and concepts related to prolonged mourning caused by the death of a spouse due to COVID-19

Discussion

This study attempted to analyze the experiences of bereaved wives losing their husbands to COVID-19. Participants could not believe the suddenness of death since unexpected grief causes an inner sorrow which cannot be treated or resolved instantly. They needed care and support to return to normal life and adapt to the new condition. They needed a distinct kind of help (35). This finding is consistent with studies which indicated that those mourning the loss of a loved one need a special kind of help to reduce their sorrow (36).

Anxiety, fear, dysfunction, and misbehavior were prevalent during the COVID-19 outbreak. However, most dysfunctions are motivated by the disruption of regular life, the resulting anxiety, and incapacitating restlessness. The participants derived notions such as avoidance, anxiety and worry, suffering and terror, loneliness, despair and alienation, fear of loneliness, and helplessness from the tragedy which befell them. This study revealed that losing a spouse leads to severe grief and loss of emotional support. Besides, the most noticeable aspect of this problem appears when a new life begins with new conditions. These findings acknowledge the fact that sorrow impairs cognitive performance (37). The sadness caused by death combined with isolation and restrictions, was a pain all participants experienced and encountered. Participants thought of instances when they wanted to be with their loved ones but could not. Therefore, their pain lingered, and all their grief remained in their hearts. They were thinking about goodbyes, sentences and words left unsaid, and there was no chance to make up for them.

Anxiety, fear, dysfunction, and misbehavior were prevalent during the COVID-19 outbreak. However, most dysfunctions are motivated by the disruption of regular life, the resulting anxiety, and incapacitating restlessness. The participants derived notions such as avoidance, anxiety and worry, suffering and terror, loneliness, despair and alienation, fear of loneliness, and helplessness from the tragedy which befell them. This study revealed that losing a spouse leads to severe grief and loss of emotional support. Besides, the most noticeable aspect of this problem appears when a new life begins with new conditions. These findings acknowledge the fact that sorrow impairs cognitive performance (37). The sadness caused by death combined with isolation and restrictions, was a pain all participants experienced and encountered. Participants thought of instances when they wanted to be with their loved ones but could not. Therefore, their pain lingered, and all their grief remained in their hearts. They were thinking about goodbyes, sentences and words left unsaid, and there was no chance to make up for them.

The COVID-19 period was far more difficult for individuals whose loved ones were ill. The patients' anguish and the pain of their loss were not insignificant, and it was exacerbated by the disease's outbreak, making them unable to grieve and settle down. Leaving them alone resulted in anxiety, psychological distress, and sadness. Deep sadness occurred when people were left alone during COVID-19. Leaving a grieving person alone is also dangerous. Participants characterized being alone as a kind of sorrow which included perpetual loss, lasting absurdity, painful agony, loneliness, and something between sadness and loneliness. These findings were consistent with previous studies. Communication skills need to be strengthened, and communication gaps should be identified. This is the best way to strengthen and consolidate the sense of cooperation (38). These results are in line with the research which suggested the impossibility of face-to-face condolence and communication limitations causes disruption in effective mourning, and then, depression in bereaved people (29).

Participants' perception of death and widowhood caused by COVID-19 also depends on their estimation of the event's danger level as a threat. Stigma or annoyance resulting from shame, pity, improper sympathy, and irony had caused the subjects the most psychological distress. These findings were similar to Esmaeilpour’s et al study which indicated that the sorrow caused by the loss of a spouse was more intense regarding the feelings of abandonment compared with the sadness caused by the death of siblings or parents (35). Grief responses are very subjective and are influenced by how the bereaved individual is supported and the degree of closeness with the departed. Individuals suffering from complicated grieving disorder recall the past and imagine a future without the departed, become immersed in despair about the future, experience an assault of unpleasant emotions, and fixate on the deceased's memories. Participants highlighted embarrassment-induced rage, hatred of the disease, remorse, and anxiety disorder as indicators of a progressive transition out of grief. These are in line with the Dehaghani's study which indicated that people who lose one or more loved ones to COVID-19 have delayed or complicated grieving due to their inability to normalize the process (39). The negative repercussions of widowhood include financial insecurity; and incompatibility with the absence of a spouse; playing the role of the father to children; being a single parent and head of the household; ignoring emotional, physical, and sexual demands; and self-sacrifice for children. It has resulted in individuals having less self-awareness, being less concerned about their health, and losing touch with themselves. It is as if their existence is determined only by the presence of males. One of the most serious challenges women encounter is the lack of financial independence and inadequate income to manage their lives. However, the most severe issue is the involvement of family and relatives in their lives and daily activities, which brings them additional agony. One of the weaknesses of this study was the lack of knowledge about participants' prior mental health status, which was not considered. Another limitation was that these families refused to participate in group counseling, and access to the participants willing to take part was very difficult. One of the limitations of the present study Focus on a specific sample (death of a spouse) was another issue. Due to the purposive sample selection, caution should be exercised in generalizing the results.

Participants' perception of death and widowhood caused by COVID-19 also depends on their estimation of the event's danger level as a threat. Stigma or annoyance resulting from shame, pity, improper sympathy, and irony had caused the subjects the most psychological distress. These findings were similar to Esmaeilpour’s et al study which indicated that the sorrow caused by the loss of a spouse was more intense regarding the feelings of abandonment compared with the sadness caused by the death of siblings or parents (35). Grief responses are very subjective and are influenced by how the bereaved individual is supported and the degree of closeness with the departed. Individuals suffering from complicated grieving disorder recall the past and imagine a future without the departed, become immersed in despair about the future, experience an assault of unpleasant emotions, and fixate on the deceased's memories. Participants highlighted embarrassment-induced rage, hatred of the disease, remorse, and anxiety disorder as indicators of a progressive transition out of grief. These are in line with the Dehaghani's study which indicated that people who lose one or more loved ones to COVID-19 have delayed or complicated grieving due to their inability to normalize the process (39). The negative repercussions of widowhood include financial insecurity; and incompatibility with the absence of a spouse; playing the role of the father to children; being a single parent and head of the household; ignoring emotional, physical, and sexual demands; and self-sacrifice for children. It has resulted in individuals having less self-awareness, being less concerned about their health, and losing touch with themselves. It is as if their existence is determined only by the presence of males. One of the most serious challenges women encounter is the lack of financial independence and inadequate income to manage their lives. However, the most severe issue is the involvement of family and relatives in their lives and daily activities, which brings them additional agony. One of the weaknesses of this study was the lack of knowledge about participants' prior mental health status, which was not considered. Another limitation was that these families refused to participate in group counseling, and access to the participants willing to take part was very difficult. One of the limitations of the present study Focus on a specific sample (death of a spouse) was another issue. Due to the purposive sample selection, caution should be exercised in generalizing the results.

Conclusion

Using the extracted categories and concepts in the design of the mourning training package can help mourners of COVID-19 and individuals and families involved in mourning. The results can also be used in bereavement training package design to prevention and support and treating other kinds of grieving. The results of this research have many applications for professionals in the field of psychotherapy and counseling. It is also effective for families dealing with the bereavement of one of their members. Accordingly, it paves the way for providing more appropriate and specialized help to people and families involved in mourning.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants who fully cooperated despite all their pain and sorrow. This article was taken from the doctoral dissertation in the counseling field at Yazd Azad University with an ethics code of IR.IAU.PS.REC.1400.092.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Authors’ contributions

H. Z M A; was involved in the interview design, extraction of the categories, and editing of the manuscript, M. K; was responsible for the research idea, interviewing, extracting the categories, interpreting and collecting data, writing, and editing the manuscript, N. S; was involved in consulting the interview methods, extracting and coding the categories, and editing the manuscript.

References

1. Howarth R. Concepts and controversies in grief and loss. Journal of mental health counseling. 2011; 33(1): 4-10.

2. Malkinson R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy of grief: A review and application. Research on Social Work Practice. 2001; 11(6): 671-698.

3. Seddighi Z, Soltani S. Prevalence of psychological disorders and mental health in working women with school children during the Covid-19 era. The first national conference on the production of health knowledge in the face of corona and governance in the post-corona world: undefined; 2021.

4. Keshvardoost S, Bahaadinbeigy K, Fatehi F. Role of telehealth in the management of COVID-19: lessons learned from previous SARS, MERS, and Ebola outbreaks. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2020.

5.Shigemura J, Ursano RJ, Morganstein JC, et al. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2020; 74(4): 281-282.

6. Yin X, Wang J, Feng J, et al. The Impact of the Corona Virus Disease 2019 Outbreak on Chinese Residents’ Mental Health. Available at SSRN 3556680. 2020.

7. Hoseini E, Zare F. Application of E-health in Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic. Journal of Community Health Research. 2020; 9(2): 66-68.

8. Shear K, Monk T, Houck P, et al. An attachment-based model of complicated grief including the role of avoidance. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience. 2007; 257(8): 453-461.

9. Tang S, Xiang Z. Who suffered most after deaths due to COVID-19 prevalence and correlates of prolonged grief disorder in COVID-19 related bereaved adults? Globalization and health. 2021; 17(1): 1-9.

10. Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, et al. Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders. 2017; 212: 138-149.

11. Eisma MC, Boelen PA, Lenferink LI. Prolonged grief disorder following the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 288: 113031.

12. Johns L, Blackburn P, McAuliffe D. COVID-19, prolonged grief disorder and the role of social work. International Social Work. 2020; 63(5): 660-4.

13. Ingles J, Spinks C, Yeates L, et al. Posttraumatic stress and prolonged grief after the sudden cardiac death of a young relative. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2016; 176(3): 402-405.

14. Boelen PA, van Denderen M, de Keijser J. Prolonged grief, posttraumatic stress, anger, and revenge phenomena following homicidal loss: the role of negative cognitions and avoidance behaviors. Homicide Studies. 2016; 20(2): 177-195

15. He L, Tang S, Yu W, et al. The prevalence, comorbidity and risks of prolonged grief disorder among bereaved Chinese adults. Psychiatry research. 2014; 219(2): 347-352.

16. Wanna R, Lueboonthavatchai P. Prevalance of complicated grief and associated factors in psychiatric outptients at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Journal of the Psychiatric Association of Thailand. 2015; 60(2): 85-98.

17. Djelantik AMJ, Smid GE, Mroz A, et al. The prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in bereaved individuals following unnatural losses: Systematic review and meta regression analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020; 265: 146-156.

18.Yi X, Gao J, Wu C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of prolonged grief disorder among bereaved survivors seven years after the Wenchuan earthquake in China: a cross-sectional study. International journal of nursing sciences. 2018; 5(2): 157-161.

19. Fujisawa D, Miyashita M, Nakajima S, et al. Prevalence and determinants of complicated grief in general population. Journal of affective disorders. 2010; 127(1-3): 352-358.

20. Maxfield M, John S, Pyszczynski T. A terror management perspective on the role of death-related anxiety in psychological dysfunction. The Humanistic Psychologist. 2014; 42(1): 35-53.

21. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry, 11th ed: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014.

22. Worden JW. Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health practitioner: springer publishing Company; 2019. 293 pp.

23. Lenferink LI, Eisma MC, Smid GE, et al. Valid measurement of DSM-5 persistent complex bereavement disorder and DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 prolonged grief disorder: The Traumatic Grief Inventory-Self Report Plus (TGI-SR+). Comprehensive psychiatry. 2022; 112: 152281.

24. Faramarzi S, Asgari K, Taghavi FJRiBS. The effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on the rate of high school students with abnormal grief. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences. 2013; 5: 373-382.

25. Goveas JS, Shear MK. Grief and the COVID-19 pandemic in older adults. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2020; 28(10): 1119-25.

26. Azim Oghlui Oskooi PB, farahbakhsh K, moradi O. Effective fields the experience of mourning after the death of a family member: A phenomenological study %J Counseling Culture and Psycotherapy. 2020; 12(45): 117-160.

27. Blankmeyer K, Hackathorn J, Bequette AW, et al. Till death do we part: Effects of mortality salience on romantic relationship factors. Unpublished manuscript, Saint Louis University. 2011.

28. Spitzenstätter D, Schnell T. Effects of mortality awareness on attitudes toward dying and death and meaning in life—a randomized controlled trial. Death Studies. 2020: 1-15.

29. Yousefi P, Ghelichpoor S, zadeh AAH, et al. The effect of coronavirus pneumonia 2019 on long-term grief disorder: A review study. The second research congress of students of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences. 2021.

30. Diolaiuti F, Marazziti D, Beatino MF, et al. Impact and consequences of COVID-19 pandemic on complicated grief and persistent complex bereavement disorder. Psychiatry Research. 2021; 300: 113916.

31. Ahmadi K, Darabi A. The effectiveness of patience training on reducing grief and facilitating posttraumatic growth. Cultural Psychology. 2017; 1(1): 114-31.

32. Mortazavi SS, Assari S, Alimohamadi A, et al. Fear, loss, social isolation, and incomplete grief due to COVID-19: a recipe for a psychiatric pandemic. Basic and clinical neuroscience. 2020; 11(2): 225.

33. Nobahari A, Fathi E, Malekshahi Beiranvand F, et al. The Death awareness and Spiritual Experience of Health Care Workers during COVID-19 Outbreak. Journal of Community Health Research 2022; 11(1): 31-35.

34. Colaizzi PF, Valle RS, King M. Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. 1978; 48-71.

35. Esmaeilpour K, Bakhshalizadeh Moradi S. The Severity of Grief Reactions Following Death of First-Grade Relatives. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2015; 20(4): 363-371.

36. Creswell JW. Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative: Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ; 2002.

37. Pérez HCS, Ikram MA, Direk N, et al. Prolonged grief and cognitive decline: a prospective population-based study in middle-aged and older persons. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2018; 26(4): 451-460.

38. Niknami M. Abbaspour A. Taghavifard M. et al. Methods of Improving the Dimensions of Psychological Empowerment of Employees of SAMT Organization in the Condition of COVID-19. Management Studies in Development and Evolution.2022; 102(30): 7-35.

39. Dehaghani FA. Evaluation of COVID-19 mourning and available treatment methods. First National Conference on Cognitive Science and Education: undefined; 2021.

Review: Applicable |

Subject:

General

Received: 2022/02/13 | Accepted: 2022/10/12 | Published: 2023/03/19

Received: 2022/02/13 | Accepted: 2022/10/12 | Published: 2023/03/19

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. |